1937 FLOOD

This is our yellow house on the Ohio River at Bay City, Illinois, a little village ten miles south of Golconda, during the ’37 flood and before renovation. You can see part of the old general store behind it that had two feet of river water in it. My father and his father both grew up in Bay City. My mother lived eight miles away.

This is the same house during the 2011 flood. Not quite as high, but you still had to boat in. And still needing lots of renovation. I was thankful. Our cabin down the road on the creek had to be gutted.

In January and February of 1937, the Ohio River flooded, big time. They called it the “Great Flood of 1937.” The Ohio River flows almost 1000 miles from its beginning in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where it is formed as the Allegheny and the Monongahela meet. Monongahela sure sounds like a Native American name. Mr. Google states it probably was a word from the Delaware Indians meaning “landslides” or “bluffs. “ Sometimes you need to sit down and see how many Indian names are used in the United States. It is a huge number. I guess the white guys didn’t want them around, but they sure liked the pretty flow of their words so kept them. Is there a song about the Cherokee, Chickasaw and the Choctaw? Well, there should be. All that beautiful alliteration. And now we name our children Cheyenne and Dakota. My granddaughter is Montana. Anyway. The cause of the flood was rainfall in January over four times the norm in just twelve days. I heard all my life about the ’37 flood from my parents. Water was everywhere.

Of course, the entire length of the river was flooded all the way to Cairo, Illinois. It was the worse flood in 175 years or on record for some sites. Damage was estimated to be over $3.3 billion or $8.7 billion, depending on the source, in current dollars. Almost 400 people died. Most all the little and big towns on both sides of the Ohio in 1937 were covered in many feet of water. Since towns were often built on the banks of the river for commerce back in the day, the business districts were still there, right down on the edge of the river. You can go in any city along the Ohio today and find oodles of pix of their town in 1937, with boats plying their way down the main street. Pictures on the walls in banks, restaurants, courthouses. And it wasn’t just a couple of feet deep. They even made post cards of flooded areas. It is a serious memory.

People had nowhere to live. They sought temporary shelters with friends, in public buildings, and, my mom told me, that in Mermet, down by Metropolis, they lived in railroad cars on the tracks. The distance from Mermet to the river is at least fifteen miles. Many towns were nearly 100% covered with river water. The entire state of Kentucky was affected. Naturally, since all the runoff collected and flowed into the river from the north, the southern areas of the Ohio had more severe flooding.

If you go down I57 heading south and get to the Big Bay/New Columbia exit north of Metropolis, look to your left. All those big flat fields were covered with water. Then think how much farther you still have to go to get to the bridge at Metropolis. That’s how far that river was out of its banks. Molly, whose parents were wonderful friends of mine and lived off this exit, told me this story. Her grandfather told her. And two people, Molly and RC Davidson, both told me that old-timers told tales that the river used to cut across there to the Mississippi. Of course, that was hundreds of years ago. The thing is, so many people were affected by this flood and were so devastated by it, that they always told their children and grandchildren stories. My father told me about taking a boat to school from Bay City, which is right on the river south of Golconda, to Cave Springs School. But, luckily, their house nor the school were flooded. Most of the houses were on a bluff or rise, or both, which saved them, but not all.

RC had several stories. He was five years old in 1937 and lived high on the bluff behind the Bay City General Store belonging to CR and Miss Tressie Weeks. The store only had two feet of water in it as did their living quarters attached to the left because they were on that Bay City bluff. CR filled ten gallon cream cans with water and put boards on top so people could walk in to the store. Then he would wade around in his hip boots to get the groceries they needed off the higher shelves. CR also tied logs in front of all the windows to keep waves from passing boats from breaking them.

RC’s aunt gave him a pair of boots. He walked on the boards, too. But when he was walking across the deep ditch at the side, he slipped and fell in over his head. That had to be cold, and he doesn’t remember how he got out. But he does remember that he got a paddling. He said the Coast Guard kindly left a boat and motor there for the people to use.

A man was staying with RC’s family because his house was flooded further up the river. So RC took a ride with him once in his boat, and they pulled up to the second story window and got out of the boat and went in the window. Amazingly, many of the flooded houses were able to be lived in after the flood, if they weren’t washed away. RC is still living in one of those houses.

There were some levees, I guess, because the song says, “Waitin’ on the levee, waitin’ for the Robert E. Lee,” and that steamboat was gone by 1876 after a collision near Natchez. But that was on the Mississippi. Shawneetown had levees for years, also back in the 19th century, but they were unreliable and often broke under the heavy rushing water. In 1937 they went down the levee a bit and blew a hole in it so it didn’t break right in town. All that water flooding on the way to Harrisburg covered the small towns in between- Junction, Equality.

The government didn’t wait too long to begin construction of new flood walls, levees, and flood gates in the disaster areas. The cost was too much to not try to prevent a rerun. In 1939, Paducah, Kentucky, began its flood control work and finished in 1949. Ten years may sound like a long time, but this system includes 9.25 miles of earthen levee, part of which is very obvious as soon as you cross the blue bridge at Brookport, and 3 miles of concrete. The concrete wall downtown at the foot of Broadway is fourteen feet high, three feet higher than the flood record. There is also a movable gate there which opens and closes to let people onto the concrete bank and to keep out the waters. It is covered with historical murals.

I hope you have been down near the river in Paducah, not just to see the murals. It is an old part of town with the old Market House and now many neat shops and eateries. It was the first time I had ever seen ice cream rolled out on a cold marble slab then scraped up. Larry thinks it was marble anyway. The sad thing is that many stores in the main downtown area, farther away from the levee and the old Market House area, are empty-big black windows. They have all moved out to the mall. When I was in eighth grade, I used to go with Regene and her parents to Paducah where we enjoyed riding the escalator in Penney’s.

Other towns around here with levees and gates are Brookport, Shawneetown, Golconda, Metropolis, and Harrisburg. In Golconda, one levee is on the east side of town to keep the river out with a gate near the levee. Then there is a gate on the west side to keep the backwaters from the creek out. And there are two on the north side of town as you head toward Eddyville. One is right on the road, but another one is right near it to keep the water out of the cemetery which sits beside the road. RC told me the Golconda system was begun in 1940 and was finished in a year and a half. That was pretty quick. Golconda is almost encircled by levees. Brookport has a levee and a gate on the east side of town. Some of these gates were closed in the flood of 2011.

I bet you didn’t know that Harrisburg used to be the twentieth largest city in Illinois before the flood, outside of the Chicago area and its suburbs. I never really thought of Harrisburg as a river town, but that land is flat all the way to Shawneetown and the river, about twenty miles. The gate is on the north side of town on the road to Eldorado, and levees go around to the east to the road to Shawneetown. There used to be a gate on that road also, but when they put the new road in they raised it over the height of the gate, so now the road runs over the top of the levee.

I asked Sarah, my daughter, why Metropolis didn’t want a levee. She said they didn’t want to mess with the view. Hmmm.

The Corps of Engineers was responsible for construction but afterwards they turned the upkeep over to the towns.

The only place that the 1937 flood does not still hold the record is in Cairo. In 2011, I worked for the Red Cross and went to Cairo for the flood. We were in a gym somewhere, but like everything else, I can’t remember if it was a church or school. I don’t think a church would have had all those bleachers. We set up cots for us volunteers and those needing shelter and tables were full of toiletries, and a myriad of other necessities for the displaced people. I can’t remember about the food, but food was always provided.

An interesting story: On that road to Shawneetown east out of Harrisburg, way down to the left below the new road where flood water would get so very deep, ergo the levee, there once sat a small building which was an adult store, seems like it was pink. It flooded big time in the 2011 flood. In 2012, I again worked with the Red Cross when the tornado went through there. This time that little building was wiped off the map. I guess somebody didn’t want it there.

I have another little story about Shawneetown in a different article, and it tells a bit more about the ‘37 flood.

And thank you to Larry, again, as usual, for downloading these pix off my phone then moving them to the story then putting the little text boxes in, resizing, etc., etc. What would I do?

PICTURES FROM THE PADUCAH FLOOD WALL

PICTURES FROM THE PADUCAH FLOOD WALL

The murals on the wall are not just about the flood, but of historical events and times in Paducah’s past. I did not take near enough pix, thy go on forever, but this can be a good thing. Maybe it will make you want to take a trip downtown to the foot of Broadway to see them all for yourself. You can walk down to the riverfront and sit on a bench or drive through and put in a boat at the ramp. You can walk along the murals and read the plaques in front of them to see what was happening. And read the names of the artists. Then back up a block and eat at one of the fantastic restaurants.

Only three years after the flood, in 1940, the Ohio River actually froze over, from bank to bank, stopping all river traffic. People walked and bicycled on the river. I have the ice skates that my father used to skate on the river.

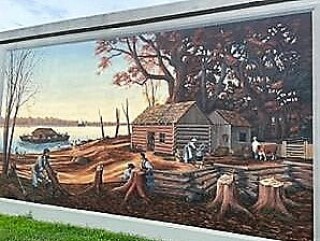

This is one of the murals.

This is the view through the wall to the river, but it is not the Broadway view where you drive through. And it is opposite the song. They are not “paving paradise to put up a parking lot.” They are tearing up the parking lot to put up a motel!

My sister Candace discovered that we have an ancestor who really did take rafts or boats down the Ohio and the Mississippi to sell boat, goods, and all before returning home with a small profit. Many, many people, including my great-grandparents and RC’s built log cabins in the Bay City river area just as in this mural. Moving west state by state.

I’m sorry this is so blurry, but after RC pulled over so I could read the plaque, I forgot to take a pic, so got this on the internet. It is Fort Anderson, and we drove by the spot near the old Executive Inn where it used to be. This was a Union fort, smack on the river, but there were many Confederate sympathizers in Paducah. It was unsuccessfully attacked by troops of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest in 1864.

This is a photo and was not on the Paducah wall, but it shows Metropolis during the flood.